If we find ourselves “apologizing” for other animals and our advocacy on their behalf, we need to ask ourselves why. Is

it an expression of self-doubt? A deliberate strategy?

Several years ago I published an article in Between the Species entitled “The Otherness of Animals.” In it, I urged that in order to avoid contributing to some of the very attitudes toward other animals that we seek to change, we need to raise fundamental questions about the way that we, as advocates for animals, actually conceive of them. One question concerns our tendency to deprecate ourselves, the animals, and our goals when speaking before the public and the press. Often we “apologize” for animals and our feelings for them: “Anxious not to alienate others from our cause, half doubtful of our own minds at times in a world that often views other animals so much differently than we do, we are liable to find ourselves presenting them apologetically at Court, spiffed up to seem more human, capable, ladies and gentlemen, of performing Ameslan (American sign language) in six languages. . . .”

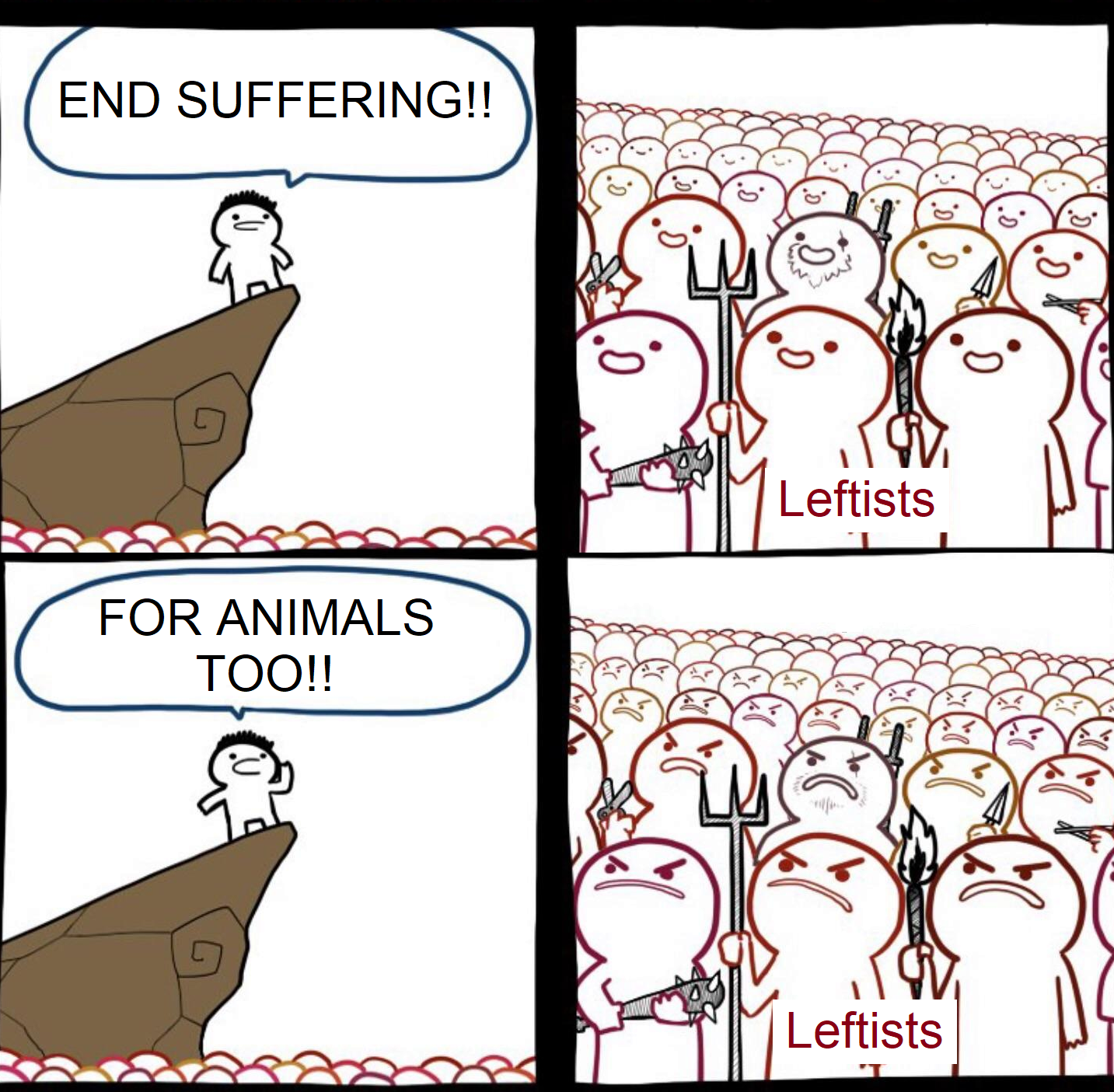

We apologize in many different ways. More than once, I’ve been warned by an animal protectionist that the public will never care about chickens, and that the only way to get people to stop eating chickens is to concentrate on things like health and the environment. However, to take this defeatist view is to create a self- fulfilling prophecy. If the spokespersons for animals decide in advance that no one will ever really care about them, or aren’t “ready” for them, this negative message will be conveyed to the public. The apologetic mode of discourse in animal rights is epitomized by the “I know I sound crazy, but . . .” approach to the public. If we find ourselves “apologizing” for other animals and our advocacy on their behalf, we need to ask ourselves why. Is it an expression of self- doubt? A deliberate strategy? Either way, I think the rhetoric of apology harms our movement tremendously. Following are some examples of what I mean.

Reassuring the public, “Don’t worry. Vegetarianism isn’t going to come overnight.” We should ask our- selves: “If I were fighting to end human slavery, child abuse or some other human-created oppression, would I seek to placate the public or the offenders by reassuring them that the abuse will still go on for a long time and that we are only trying to phase it out gradually?” Why, instead of defending a vegan diet, are we not affirming it? Patronizing animals: “Of course they’re only animals, but . . .” “Of course they can’t reason the way we do. Of course they can’t appreciate a symphony or paint a great work of art or go to law school, but . . .” In fact, few people live their lives according to “reason,” or appreciate symphonies or paint works of art.

As human beings, we do not know what it feels like to have wings or to take flight from within our own bodies or to live naturally within the sea. Our species represents a smidgeon of the world’s experience, yet we patronize everything outside our domain. Comparing the competent, adult members of other animal species with human infants and cognitively impaired humans. Do we really believe that all of the other animals in this world have a mental life and range of experience comparable to diminished human capacity and the sensations of human infants? Except within the legal system, where all forms of life that are helpless against human assault should be classed together and defended on similar grounds, this analogy is both arrogant and absurd.

Starting a sentence with, “I know these animals aren’t as cute as other animals, but . . .” Would you tell a child, “I know Billy isn’t as cute as Tom, but you still have to play with him”? Why put a foregone conclusion in people’s minds? Why even suggest that physical appearance and conventional notions of attractiveness are relevant to how someone should be treated? Letting ourselves be intimidated by “science says,” “producers know best,” and charges of “anthropomorphism.”

We are related to other animals through evolution. Our empathic judgments reflect this fact. It doesn’t take special credentials to know, for example, that a hen confined in a wire cage is suffering, or to imagine what her feelings must be compared with those of a hen ranging outside in the grass. We’re told that humans are capable of knowing just about anything we want to know – except what it feels like to be one of our victims. Intellectual confidence is needed here, not submission to the epistemological deficiencies, cynicism, and intimidation tactics of profiteers.

Letting others identify and define who we are. I once heard a demonstrator tell a member of the press at a chicken slaughterhouse protest, “I’m sure Perdue thinks we’re all a bunch of kooks for caring about chickens, but . . .” Ask yourself: Does it matter what the Tysons and Perdues of this world “think” about anything? Can you imagine Jim Perdue standing in front of a camera, saying, “I know the animal rights people think I’m a kook, but . . .”? Needing to “prove” that we care about people, too. The next time someone challenges you about not caring about people, politely ask them what they’re working on. Whatever they say, say, “But why aren’t you working on ________?” “Don’t you care about ________?”

We care deeply about many things, but we cannot devote our primary time and energy to all of them. We must focus our attention and direct our resources. Moreover, to seek to enlarge the human capacity for justice and compassion is to care about and work for the betterment of people. Needing to pad, bolster and disguise our concerns about animals and animal abuse. An example is: “Even if you don’t care about roosters, you should still be concerned about gambling” in arguments against removedfighting. Is animal advocacy consistent with reassuring people that it’s okay not to care about the animals involved in animal abusing activities? That the animals themselves are “mere emblems for more pressing matters”? Instead, how about: “In addition to the horrible suffering of the roosters, there is also the gambling to consider.” Expanding the context of concern is legitimate. Diminishing the animals and their plight to gain favor isn’t. In recognizing the reality of other societal concerns, it is imperative to recognize that the abuse of animals is a human problem as serious as any other. Unfortunately, the victims of homo sapiens are legion. As individuals and groups, we cannot give equal time to every category of abuse. We must go where our heartstrings pull us the most, and do the best that we can with the confidence needed to change the world.

Be Affirmative, Not Apologetic

The rhetoric of apology in animal rights is an extension of the “unconscious contributions to one’s undoing” described by the child psychologist, Bruno Bettelheim.* He pointed out that human victims will often collaborate unconsciously with an oppressor in the vain hope of winning favor. An example in the animal rights movement is reassuring others that you still eat meat, or don’t oppose hunting, as a “bonding” strategy to get them to support a ban on, say, animal testing. Ask yourself if using one group of exploited animals as bait to win favor for another really advances our cause.

In fighting for animals and animal rights – the claims of other animals upon us as fellow creatures with feelings and lives of their own – against the collective human oppressor, we assume the role of vicarious victims. To “apologize” in this role is to betray “ourselves” profoundly. We need to understand why and how this can happen. As Bettelheim wrote, “But at the same time, understanding the possibility of such unconscious contributions to one’s undoing also opens the way for doing something about the experience – namely, preparing oneself better to fight in the external world against conditions which might induce one unconsciously to facilitate the work of the destroyer.” We must prepare ourselves in this way. If we feel that we must apologize, let us apologize to the animals, not for them.

*Bruno Bettelheim, “Unconscious Contributions to One’s Undoing,” SURVIVING and Other Essays, Vintage Books, 1980