philosophy

Other philosophy communities have only interpreted the world in various ways. The point, however, is to change it. [ x ]

"I thunk it so I dunk it." - Descartes

Short Attention Span Reading Group: summary, list of previous discussions, schedule

Will shared resources always be misused and overused? Is community ownership of land, forests and fisheries a guaranteed road to ecological disaster? Is privatization the only way to protect the environment and end Third World poverty? Most economists and development planners will answer “yes” — and for proof they will point to the most influential article ever written on those important questions.

Since its publication in Science in December 1968, “The Tragedy of the Commons” has been anthologized in at least 111 books, making it one of the most-reprinted articles ever to appear in any scientific journal. It is also one of the most-quoted: a recent Google search found “about 302,000” results for the phrase “tragedy of the commons.”

For 40 years it has been, in the words of a World Bank Discussion Paper, “the dominant paradigm within which social scientists assess natural resource issues.” (Bromley and Cernea 1989: 6) It has been used time and again to justify stealing indigenous peoples’ lands, privatizing health care and other social services, giving corporations ‘tradable permits’ to pollute the air and water, and much more.

Noted anthropologist Dr. G.N. Appell (1995) writes that the article “has been embraced as a sacred text by scholars and professionals in the practice of designing futures for others and imposing their own economic and environmental rationality on other social systems of which they have incomplete understanding and knowledge.”

Like most sacred texts, “The Tragedy of the Commons” is more often cited than read. As we will see, although its title sounds authoritative and scientific, it fell far short of science.

Garrett Hardin hatches a myth

The author of “The Tragedy of the Commons” was Garrett Hardin, a University of California professor who until then was best-known as the author of a biology textbook that argued for “control of breeding” of “genetically defective” people. (Hardin 1966: 707) In his 1968 essay he argued that communities that share resources inevitably pave the way for their own destruction; instead of wealth for all, there is wealth for none.

He based his argument on a story about the commons in rural England.

(The term “commons” was used in England to refer to the shared pastures, fields, forests, irrigation systems and other resources that were found in many rural areas until well into the 1800s. Similar communal farming arrangements existed in most of Europe, and they still exist today in various forms around the world, particularly in indigenous communities.)

“Picture a pasture open to all,” Hardin wrote. A herdsmen who wants to expand his personal herd will calculate that the cost of additional grazing (reduced food for all animals, rapid soil depletion) will be divided among all, but he alone will get the benefit of having more cattle to sell.

Inevitably, “the rational herdsman concludes that the only sensible course for him to pursue is to add another animal to his herd.” But every “rational herdsman” will do the same thing, so the commons is soon overstocked and overgrazed to the point where it supports no animals at all.

Hardin used the word “tragedy” as Aristotle did, to refer to a dramatic outcome that is the inevitable but unplanned result of a character’s actions. He called the destruction of the commons through overuse a tragedy not because it is sad, but because it is the inevitable result of shared use of the pasture. “Freedom in a commons brings ruin to all.”

Where’s the evidence?

Given the subsequent influence of Hardin’s essay, it’s shocking to realize that he provided no evidence at all to support his sweeping conclusions. He claimed that the “tragedy” was inevitable — but he didn’t show that it had happened even once.

Hardin simply ignored what actually happens in a real commons: self-regulation by the communities involved. One such process was described years earlier in Friedrich Engels’ account of the “mark,” the form taken by commons-based communities in parts of pre-capitalist Germany:

“[T]he use of arable and meadowlands was under the supervision and direction of the community …

“Just as the share of each member in so much of the mark as was distributed was of equal size, so was his share also in the use of the ‘common mark.’ The nature of this use was determined by the members of the community as a whole. …

“At fixed times and, if necessary, more frequently, they met in the open air to discuss the affairs of the mark and to sit in judgment upon breaches of regulations and disputes concerning the mark.” (Engels 1892)

Historians and other scholars have broadly confirmed Engels’ description of communal management of shared resources. A summary of recent research concludes:

“[W]hat existed in fact was not a ‘tragedy of the commons’ but rather a triumph: that for hundreds of years — and perhaps thousands, although written records do not exist to prove the longer era — land was managed successfully by communities.” (Cox 1985: 60)

Part of that self-regulation process was known in England as “stinting” — establishing limits for the number of cows, pigs, sheep and other livestock that each commoner could graze on the common pasture. Such “stints” protected the land from overuse (a concept that experienced farmers understood long before Hardin arrived) and allowed the community to allocate resources according to its own concepts of fairness.

The only significant cases of overstocking found by the leading modern expert on the English commons involved wealthy landowners who deliberately put too many animals onto the pasture in order to weaken their much poorer neighbours’ position in disputes over the enclosure (privatization) of common lands. (Neeson 1993: 156)

Hardin assumed that peasant farmers are unable to change their behaviour in the face of certain disaster. But in the real world, small farmers, fishers and others have created their own institutions and rules for preserving resources and ensuring that the commons community survived through good years and bad.

Why does the herder want more?

Hardin’s argument started with the unproven assertion that herdsmen always want to expand their herds: “It is to be expected that each herdsman will try to keep as many cattle as possible on the commons. … As a rational being, each herdsman seeks to maximize his gain.”

In short, Hardin’s conclusion was predetermined by his assumptions. “It is to be expected” that each herdsman will try to maximize the size of his herd — and each one does exactly that. It’s a circular argument that proves nothing.

Hardin assumed that human nature is selfish and unchanging, and that society is just an assemblage of self-interested individuals who don’t care about the impact of their actions on the community. The same idea, explicitly or implicitly, is a fundamental component of mainstream (i.e., pro-capitalist) economic theory.

All the evidence (not to mention common sense) shows that this is absurd: people are social beings, and society is much more than the arithmetic sum of its members. Even capitalist society, which rewards the most anti-social behaviour, has not crushed human cooperation and solidarity. The very fact that for centuries “rational herdsmen” did not overgraze the commons disproves Hardin’s most fundamental assumptions — but that hasn’t stopped him or his disciples from erecting policy castles on foundations of sand.

Even if the herdsman wanted to behave as Hardin described, he couldn’t do so unless certain conditions existed.

There would have to be a market for the cattle, and he would have to be focused on producing for that market, not for local consumption. He would have to have enough capital to buy the additional cattle and the fodder they would need in winter. He would have to be able to hire workers to care for the larger herd, build bigger barns, etc. And his desire for profit would have to outweigh his interest in the long-term survival of his community.

In short, Hardin didn’t describe the behaviour of herdsmen in pre-capitalist farming communities — he described the behaviour of capitalists operating in a capitalist economy. The universal human nature that he claimed would always destroy common resources is actually the profit-driven “grow or die” behaviour of corporations.

Will private ownership do better?

That leads us to another fatal flaw in Hardin’s argument: in addition to providing no evidence that maintaining the commons will inevitably destroy the environment, he offered no justification for his opinion that privatization would save it. Once again he simply presented his own prejudices as fact:

“We must admit that our legal system of private property plus inheritance is unjust — but we put up with it because we are not convinced, at the moment, that anyone has invented a better system. The alternative of the commons is too horrifying to contemplate. Injustice is preferable to total ruin.”

The implication is that private owners will do a better job of caring for the environment because they want to preserve the value of their assets. In reality, scholars and activists have documented scores of cases in which the division and privatization of communally managed lands had disastrous results. Privatizing the commons has repeatedly led to deforestation, soil erosion and depletion, overuse of fertilizers and pesticides, and the ruin of ecosystems.

As Karl Marx wrote, nature requires long cycles of birth, development and regeneration, but capitalism requires short-term returns. -

The rest of the article is in the link (no space for the rest)

I tried it recently. It worked. Problem, contrarian in the back row? :troll:

idfk looks cool or smthjng

A cocktail of elite arrogance and naivete across the Anglophone world, combined with the support of billionaires like Sam Bankman-Fried, produced effective altruism. The result has been reactionary, often racist intellectual defenses of inequality.

According to Karl Marx, a combination of arrogance and ignorance incubated in elite institutions was to blame for the worst excesses of British moral philosophy. The same holds true for effective altruism.

:marx-hi:

Academics are fond of giving lofty names to their research institutions. But the Future of Humanity Institute, a research body based at Oxford University, is grandiose even by the standards of an elite institution that takes it for granted that many of its graduates will go on to walk the halls of power.

The combination of a forward-looking outlook and a universalist perspective would suggest that the institute would at the very least be home to cosmopolitan and egalitarian ideas. For this reason, it came as a surprise to some when a racist email written by Nick Bostrom, a professor at the institute, resurfaced. In the email, sent in 1996 to a transhumanist mailing list of which Bostrom was a member, the future Oxford don writes that “blacks are more stupid than whites” and then later doubles down enthusiastically on this statement by telling the forum’s members, “I like that sentence and think it’s true.”

In the email, Bostrom cites as evidence for his assertions “scientific” views about IQ differences between racial groups. Predictably, he suggests that fear of being accused of bigotry prevents honest talk about these important issues: “For most people, however, the sentence seems to be synonymous with: ‘I hate those bloody n——!!!,’” he wrote.

Given this concern, he concludes there’s a need for caution in communicating the “facts” about relative mental inferiority in ways that don’t invite accusations of racism and therefore result in “personal damage.” He is adamant that he’s not racist, and he seems to sincerely believe this claim.

We might think that, given the incident took place decades ago, it is hardly relevant. This may have been the case were it not for the fact that, in an apology circulated by Bostrom earlier this month, he did little to challenge the central claims of his previous racist rant. “I completely repudiate this disgusting email from 26 years ago,” Bostrom writes:

It does not accurately represent my views, then or now. The invocation of a racial slur was repulsive. I immediately apologized for writing it at the time, within 24 hours; and I apologize again unreservedly today. I recoil when I read it and reject it utterly.

The main problem, according to Bostrom, was the use of a racial slur and not, his statement suggests, his commitment to pseudoscientific ideas about racial difference.

Bostrom is an advocate of longtermism, a once-niche concept now in vogue thanks to a bestselling 2022 book, What We Owe the Future, by William MacAskill, a pioneer of the effective altruism (EA) movement. The gist of longtermism is that future people, however distant, have equal moral value to people alive today. Though seemingly innocuous, this view has drawn support from reactionary conservatives and tech gurus who flood Bostrom and MacAskill with millions in research grants.

What is it about effective altruism and offshoots like longtermism that make them so appealing to tech billionaires who flood MacAskill and his pals with grants, book endorsements, and invitations to California retreats?

The short answer is that effective altruism, for all the hype about being a novel, game-changing approach, is at heart a conservative movement, which attempts to present billionaires as a solution to global poverty rather than its cause. The effective altruism movement has parasitically latched onto the back of the billionaire class, providing the ultrarich with a moral justification of their position.

In a 2015 conference hosted by Google, organizers enthused that “effective altruism could be the last social movement we ever need.” A deeply implausible statement, of course, but one that has managed somehow to serve as a rallying cry for the idealistic rich.

Rooted in a worldview that stretches from philosopher Peter Singer to the grandaddy of consequentialism, Jeremy Bentham (“Bentham’s bulldog” is the title of one effective altruism fan’s Substack), proponents of effective altruism champion the belief that measurable effects in terms of lives saved is the only rational way to make decisions about philanthropic expenditures.

In many ways, their interest in measurement is not particularly objectionable, nor new. Gilded Age robber barons like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller drew upon Taylorist management principles to insist that their giving was more scientific than earlier philanthropists. In every age, we see apologetics for extreme, concentrated wealth, and while the charitable causes shift, the rationales tend to be pretty much the same: my extreme wealth is good — no matter how concentrated and disproportionate — because others will inevitably benefit from it — if not today, then certainly tomorrow.

“Earn to give” is the most recent instantiation of the supposedly rational justification of inequality. It’s the idea that people are morally beholden to maximize wealth however possible so they have more to give, leading in its most extreme interpretation to the insistence there may be no moral “good” after all in trying to save poor lives, because rich people are more “innovative” and thus more worthy.

“It now seems more plausible to me that saving a life in a rich country is substantially more important than saving a life in a poor country, other things being equal,” wrote Nick Beckstead in his 2013 Rutgers PhD, which he completed before joining the Future of Humanity Institute as a research fellow and then going on to work as CEO of the FTX Foundation before leaving in the wake of Sam Bankman-Fried’s recent disgrace.

Certainly, not everyone in the effective altruism movement agrees with Beckstead’s claim that saving rich lives is worthier than saving poor ones. It is, however, those like him with the most extremist, pro-rich takes on trickle-down policies who seem to get the plum jobs at effective altruism research centers. On EA forums, meanwhile, hoi polloi frustration is mounting. There is growing realization that a hierarchical movement spearheaded by a handful of mediagenic men and the billionaires they worship might not be the world’s saviors after all.

Many onetime enthusiasts who read books like MacAskill’s first one, Doing Good Better, and were inspired to “give what we can” are frustrated. They earnestly wanted to help poorer groups and feel cheated. They are right to feel that way. Given their sincerity, it feels almost cruel to break the news: no, you’re not the last social movement humanity will ever need. Indeed, many seem to have little knowledge of previous ones, a problem I encountered when I worked as a research fellow in Oxford and met EA leaders in the early days of the movement.

At first, I thought we shared a common cause. Before reaching Oxford, I’d been a journalist and activist, reporting on movements calling for reform to global trade policies that hindered poor nations from acquiring pharmaceuticals, domestic tax revenue, and the policy freedom they deserved. Many of the effective altruism proponents I met, meanwhile, spoke about ending global poverty but had never heard of the World Trade Organization (WTO) or the International Monetary Fund (IMF). This ignorance seemed not to perturb but to embolden them to make grand claims about the “facts” of the global economy.

“The Moral Case for Sweatshop Goods,” a chapter in MacAskill’s first book, hails sweatshop labor as an unalloyed advantage, even a beneficent gift, to poor nations: “Among economists on both the left and the right, there is no question that sweatshops benefit those in poor nations.” The authorities he cites are Paul Krugman and Jeffrey Sachs. His main empirical material appears to be drawn from Nicholas Kristof’s New York Times columns. “I’d love to get a job in a factory,” one Cambodian woman says to Kristof.

To be sure, you can find some economists across the spectrum to defend sweatshops. But you can also find reams of Global South scholarship on tax drain and the bullying of nations to accept draconian IMF loan conditions. MacAskill’s book entirely ignores any viewpoint that does not affirm his own conservative priors — perhaps because confronting alternative views might force a rethinking of his philosophical stance, which is predicated on exhorting the world’s 1 percent to engage in as much economic predation of poor groups as possible as long it generates private wealth to then disburse.

MacAskill’s strategic ignorance is not unusual; it is in fact hardwired into the history of the branch of Anglophone philosophy out of which effective altruism emerged. James Mill, the father of John Stuart Mill, published a history of India in 1817 that helped him to be upheld as a key global authority on the nation, later taking up senior positions in the East India Company. Incredibly, he purposely chose not to visit India while writing his three-volume history because he didn’t want to be biased by local norms. As the Nobel Prize–winning economist Amartya Sen put it, “Mill seemed to think that this non-visit made his history more objective.”

This sort of insipid, purposeful blindness tended to enrage later anti-utilitarian thinkers like Friedrich Nietzsche and Karl Marx. It’s probably why Marx voiced sharp criticism of Bentham, who he called that “arch-philistine . . . that soberly pedantic and heavy-footed oracle of the ‘common sense’ of the nineteenth-century bourgeoisie.”

Frantz Fanon, born on this day in 1925, was a West Indian Pan-Africanist philosopher and Algerian revolutionary most known for his text The Wretched of the Earth.

Fanon was born to an affluent family on the Caribbean island of Martinique, then a French colony which is still under French control today. As a teenager, he was taught by communist anti-colonial thinker Aimé Césaire (1913 - 2008).

Fanon was exposed to much European racism during World War II. After France fell to the Nazis in 1940, a Nazi government was set up in Martinique by French collaborators, whom he describedas taking off their masks and behaving like "authentic racists".

Fighting for the Allied forces, Fanon also observed European women liberated by black soldiers preferring to dance with fascist Italian prisoners rather than fraternize with their liberators.

While completing a residency in psychiatry in France completing, Fanon wrote and published his first book, "Black Skin, White Masks" (1952), an analysis of the negative psychological effects of colonial subjugation upon black people.

Following the outbreak of the Algerian revolution in November 1954, Fanon joined the Front de Libération Nationale, a nationalist Algerian party. Working at a French hospital in Algeria, Fanon became responsible for treating the psychological distress of the French troops who carried out torture to suppress anti-colonial resistance, as well as their Algerian victims.

While organizing for Algerian independence in Ghana, Fanon was diagnosed with leukemia that would ultimately kill him. He spent the last year of his life writing his most famous work, "The Wretched of the Earth" (French: Les Damnés de la Terre). The text provides a psychiatric analysis of the dehumanizing effects of colonization and examines the possibilities of anti-colonial liberation

Following a trip to the Soviet Union to treat his leukemia, Fanon came to the U.S. in 1961 for further treatment in a visit arranged by the CIA. Fanon died in Bethesda, Maryland on December 6th, 1961 under the name of "Ibrahim Fanon", a Libyan nom de guerre he had assumed in order to enter a hospital after being wounded during a mission for the Algerian National Liberation Front.

"In the World through which I travel, I am endlessly creating myself."

-

Frantz Fanon

-

Biography :fanon:

Megathreads and spaces to hang out:

- ❤️ Come listen to music with your fellow Hexbears in Cy.tube

- 💖 Come talk in the New weekly queer thread

- 🧡 Monthly Neurodiverse Megathread

- 💛 Read about a current topic in the news

- ⭐️ May Movie Schedule ⭐️

reminders:

- 💚 You nerds can join specific comms to see posts about all sorts of topics

- 💙 Hexbear’s algorithm prioritizes struggle sessions over upbears

- 💜 Sorting by new you nerd

- 🌈 If you ever want to make your own megathread, you can go here nerd

Links To Resources (Aid and Theory):

Aid:

- 💙Comprehensive list of resources for those in need of an abortion -- reddit link

- 💙Resources for Palestine

Theory:

I can't believe people still believe in free will and agency. I'm not aware of anything in biology or physics that suggests we have some magic spark in a mystical plane that gives us "free will". We just do stuff in response to stimulus. I would have thought this debate would die when neurologists started opening up people's brains and inducing massive personality shifts and various cognitive aberrations by poking people's brain meat with electrodes. It's just a false dichotomy left over from weird medieval religious nonsense.

God they're talking about choosing to act Killllll meeeeeee

I'm reading the intro to Infinite Thought btws feel free to check in here because I will be cataloging my distress relating to French people who spend too much time thinking and not enough time practicing with swords.

Nick Land's drugs got him there well before everyone else, but I'm talking about the right wing cranks such as Big Yud that have kept up a mask of "grey tribe" pretenses, said stupid stale memes like "politics is the mind killer," and worshipped billionaires as the more radiant energy beings they are, being of the sky while we are of the dirt.

Sure, it seemed inevitable all along, especially when billionaires started outright buying ownership stakes in "futurology" conventions. It got especially creepy when the United States Department of Defense openly peddled contractor wares in such places.

It isn't fun being the Cassandra, seeing it happening in real time, warning people, then getting laughed off about it. I've lost real life friends to this stuff, people that were superficially just open minded and quirky in college but now wear the metaphorical armband and goosestep to wherever Sam Harris or other crypto-bigoted cranks tell them to go.

youtube links at the site for each of these lectures:

Course Outlines and Lecture Notes

100 Philosophy and Human Values (1990)

200 Nietzsche and the Postmodern Condition (1991)

300 The Self Under Siege (1993)

Lecture List

101 Socrates and the Life of Inquiry (1990)

102 Epicureans, Stoics, Skeptics (1990)

103 Kant and the Path to Enlightenment (1990)

104 Mill on Liberty (1990)

105 Hegel and Modern Life (1990)

106 Nietzsche: Knowledge and Belief (1990)

107 Kierkegaard and the Contemporary Spirit (1990)

108 Philosophy and Post-Modern Culture (1990)

201 Nietzsche as Myth and Mythmaker (1991)

202 Nietzsche on Truth and Lie (1991)

203 Nietzsche as Master of Suspicion and Immoralist (1991)

204 Nietzsche: The Death of God (1991)

205 Nietzsche: The Eternal Recurrence (1991)

206 Nietzsche: The Will to Power (1991)

207 Nietzsche as Artist (1991)

208 Nietzsche’s Progeny (1991)

301 Paul Ricoeur: The Masters of Suspicion (1993)

302 Heidegger and the Rejection of Humanism (1993)

303 Sartre and the Roads to Freedom (1993)

303 Sartre and the Roads to Freedom v2 (1993)

304 Marcuse and One-Dimensional Man (1993)

305 Habermas and the Fragile Dignity of Humanity (1993)

306 Foucault and the Disappearance of the Human (1993)

307 Derrida and the Ends of Man (1993)

308 Baudrillard: Fatal Strategies (1993)

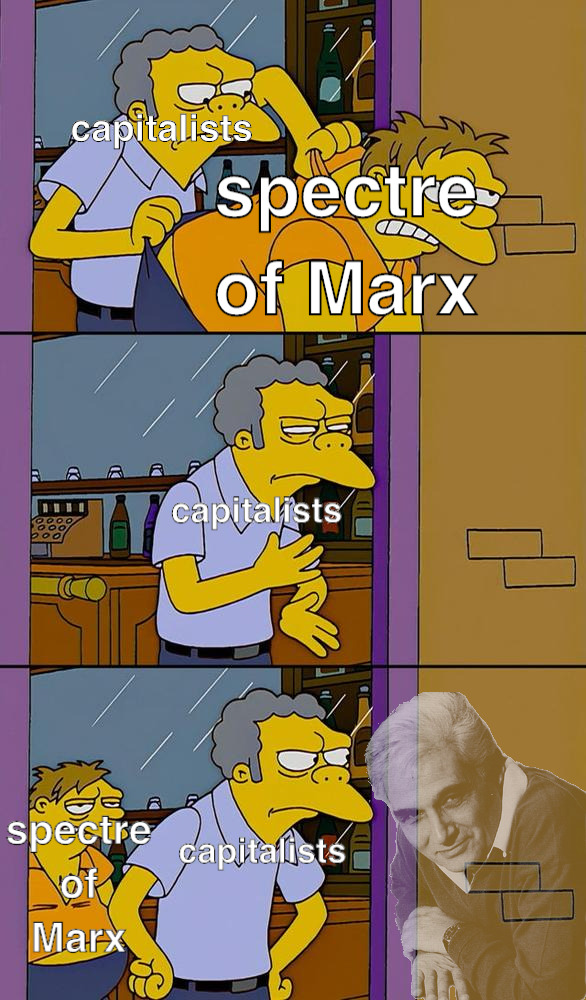

It's time to continue our Memes with Citations series with my favorite work by everybody's poster child of postmodern literary theory, Jacques Derrida. His entire shtick, in a nutshell, is a continuation of Marxist materialism into the literary sphere that he called "deconstruction." Truth, justice, fact? All hogwash—all that exists is the sign, and signs derive meaning via contrast with other signs. "There is no outside-text," and all meaning must exist in conversation with everything else. This is all great and fun, but we're here to talk about his "political turn" in the 90's, and specifically his Spectres of Marx.

He wrote the book in 1993, after the collapse of actually existing communism with the left in total disarray. It was the "end of history" as Fukuyama declared, and neoliberalism was the "one true" system left. Not so fast, wrote Derrida. As he explains (and this is the meme):

Capitalist societies can always heave a sigh of relief and say to themselves: communism is finished since the collapse of the totalitarianism of the twentieth century and not only is it finished, but it did not take place, it was only a ghost. They do no more than disavow the undeniable itself: a ghost never dies, it remains always to come and to come-back.

Through this comment, the study of hauntology was born. A ghost from the past, haunting the present with a promised future that never came. It's been applied to all sorts of things, from music (see Mark Fisher's Ghosts of My Life) to climate change (by yours truly), but the kernel of the study is that Marxism will forever haunt the West, for it can never be truly killed.

The gall that Derrida has to write this book is amazing, for it seemed all was lost for the worldwide left. Destroyed in Europe, in retreat everywhere else, it was truly the end times. And here was this literary theorist, the boogeyman of the culture wars of the 80's and 90's, writing about how communism can never truly be killed.

Want to also share the following passage, which I think is the best arguement against capitalism in the modern era ever formulated. For every chud that screams at you that "poverty has never been lower," just tell them something like the following:

For it must be cried out, at a time when some have the audacity to neo-evangelise in the name of the ideal of a liberal democracy that has finally realised itself as the ideal of human history: never have violence, inequality, exclusion, famine, and thus economic oppression affected as many human beings in the history of the earth and of humanity. Instead of singing the advent of the ideal of liberal democracy and of the capitalist market in the euphoria of the end of history, instead of celebrating the ‘end of ideologies’ and the end of the great emancipatory discourses, let us never neglect this obvious macroscopic fact, made up of innumerable singular sites of suffering: no degree of progress allows one to ignore that never before, in absolute figures, have so many men, women and children been subjugated, starved or exterminated on the earth.